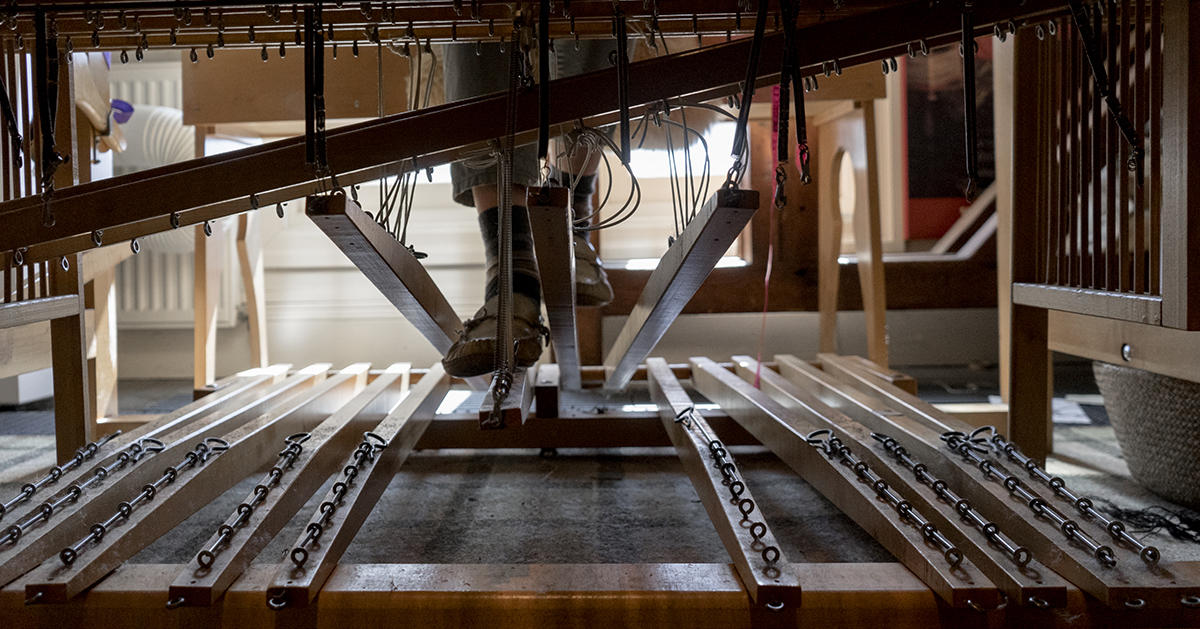

Deborah’s studio is a magical space tucked away in the attic of her Toronto home. Filled with weaving equipment and cones of yarn, there is something to pique your interest everywhere you look. Deborah’s weaving practice draws on 19th century Canadian weaving, often using materials locally produced in Ontario.

Written and photographed by Emily Neill

When did you start weaving?

I was interested in a variety of textile crafts from an early age. I dabbled in crocheting, rug hooking, knitting, macrame and quilting until I discovered weaving which thereafter dominated my textile interests. I discovered weaving as a teenager, on my way to and from a job I had in Oakville, I would pass by a shop called Sue-Sam Products which I was attracted to because there was a spinning wheel in the window display. I went in one day and signed up for a class in spinning and weaving. I took to the equipment and the process immediately. The owner, Stella Gopsill was a fabulous and encouraging teacher. Because of her support, I enrolled in the Textile Program at the Ontario College of Art where I majored in woven textiles.

Where do you draw your passion for weaving from?

I have always been attracted to making ‘something from nothing.’ As a child, I was curious about how things originated. Learning about making cloth which is so multi-stepped and ancient, that is starting with something as simple as string and using equipment that is essentially sticks and ropes, really satisfies the urge to start from the beginning. I developed an interest in 19th century textiles from eastern Canada because I wanted to know about the textiles people made before my time. These textiles, made in eastern Canada, represent the tail end of a long tradition of preindustrial production of cloth on horizontal looms inherited by professional weavers from Scotland, England, Ireland and Germany. These weavers, displaced by mechanized textile production beginning in the mid 18thcentury, relocated to North America where they continued their work in their profession of choice, handloom weaving. Their knowledge of weaving is contained in the material culture and documents that survive from 19th century eastern Canada which I draw on as my sources and inspiration.

Can you tell me about a few of the projects you are working on at the moment?

I’m working on a few interesting projects right now. I’m weaving a yardage of tweed for a three piece suit for Rajiv Surendra. I met Rajiv in 2000 when I was working at Black Creek Pioneer Village. Rajiv who had an interest in historical crafts and trades at a young age was volunteering at Black Creek as a young teen when I met him. Over the years, I have had the pleasure of making several pieces for Rajiv. We thought it would be so amazing to create fabric using wool raised, milled and woven in Ontario as a truly Upper Canadian suit. It was just talk at first – then we decided, let’s make it happen. The wool we’re using is undyed dark brown and medium brown wool from Pine Hollow Farm in Norwood, Ontario. The singles were spun at Wellington Fibres in Elora. Rajiv will get it tailored in Manhattan – interestingly, the suit will be first tailored at Coppley Apparel in Hamilton before making its way to New York where the finishing touches will be completed. I’m weaving the tweed on a handloom in herringbone using a flying shuttle (the flying shuttle was invented in 1733 by John Kay).

I also have two museum reproductions on the go. One is for Upper Canada Village in Morrisburg, Ontario. I’m weaving a 4 panel floatwork carpet. Floatwork is a structure commonly used for 19th century coverlets (the decorative top blanket on a bed), but it is also found on carpets and table linens. For this carpet, I will be using wool from a heritage breed, Dorset sheep. The wool from Dorset sheep has long staples that are relatively smooth and thick. This quality of fibre is essential for carpets as it makes the wool stand up to foot traffic. After the wool is custom spun by Wellington Fibres, I will have it small batch dyed by Liam Blackburn an expert in dyeing from natural and foraged dyestuff. This project will be completed by about August and the carpet will be in the Pastor’s House at Upper Canada Village.

The second reproduction is two rag carpets for Montgomery’s Inn in Toronto. Hand woven textiles produced in 19th century Ontario were part of a customer/weaver partnership. For the Montgomery’s Inn carpets, I did a training session with staff in rag strip joining. Staff will join the rest of the strips with visitors to the museum who will learn about this important part of the 19th century household economy. In the 19th century, it was commonplace for customers to be involved in some of the pre- and post-weaving production which included tasks like joining fabric strips for rag carpets. Customers would bring balls of joined strips to the weaver for weaving. Just as in the 19th century, when the strips are joined, they are given to the weaver to be woven up into the finished product. This project will be completed about September. The carpets will be located in the Boys’ Room and the Travellers’ Sitting Room of Montgomery’s Inn.

What is involved in the process of weaving?

Weaving in its simplest form is when horizontal threads (weft) travel under and over vertical threads (warp) for one row and then turn around and travel over and under for the next row, followed by as many repeats as needed for the length required. Depending on the tradition, there is a wide variety of methods used to achieve weaving. Our tradition in Ontario is connected to the European tradition of horizontal loom weaving that stretches back to about 12th century Europe. The horizontal loom originally comes from China. This technology was brought to Europe and replaced the vertical loom which continued to persist in Scandinavia and Scotland until about the 17th century in some areas and as late as the 20th century in Lapland in Scandinavia. Weaving on a horizontal loom was a great time saver for the actual weaving. The saving in time was a result of the set up which allowed for the picking up of the threads in a set instead of one at a time. Essentially, our handlooms today aren’t so very different from those early horizontal looms.

You use a lot of local materials, what kind of fibres do you have access to and why is that important to you?

I really try to use as much locally sourced and processed fibre as possible, with the exception of cotton which does not grow in our fibreshed. Linen, although once grown in Ontario, is also not currently available in production quantities. The fibre I have access to is wool, mohair and alpaca. The interesting thing about using regional wool and specific breeds is that the different types of wool and alpaca have specific qualities which lend themselves to different applications. Depending on these qualities, different results emerge. Fortunately, Donna Hancock from Wellington Fibres is able to guide me to using the most appropriate fibre for the final product. Using local fibre is so meaningful to me because of my interest in period textiles. Historically, these textiles would have been produced using locally raised and processed fibre. It’s so wonderful to make those connections again between the textiles of the past and local fibre in our fibreshed. I deeply thank Peggy Sue Deaven-Smiltnieks for introducing me to using local fibre when I started working with her in 2016.

What does the landscape of weaving in Ontario look like?

Today, there is a great deal of enthusiasm about supporting local food at farmers markets. This food awareness has spread to other areas such as fashion. The environmental and social costs of buying fast fashion is prompting people to think again about the implications of the current fashion market. There’s a growing awareness that buying sustainable and when possible, local textiles is important, however, the cost of paying a fair wage is still a little shocking to the consumer who is accustomed to purchasing garments for shockingly low prices.

Producing textiles, is a time consuming endeavour hence the great cost of textiles previous to mechanization. In the 19th and early 20th century, Ontario had a fairly vibrant textile industry. As Canadian companies struggled to compete, textile mills closed down leaving us with a very pared down textile industry. The only companies that survived were the ones that went high tech. As a result, we don’t have the inbetween, medium-sized mills. There are production handloom weavers out there, but prices can be prohibitive for most people. Fortunately, in terms of mill carding and spinning, we have a few mills spinning animal fibre. Interestingly, in the past, it was carding and spinning mechanization that preceded weaving mechanization. In a way, this knowledge is comforting as we move towards building up our textile production technology in Ontario starting with carding and spinning mechanization followed by weaving mechanization.

Do you see this landscape changing in the future?

I think it will continue to grow at a slow and measured pace. And, that’s actually a good thing. The problem with accelerated growth as was the case with large scale mill weaving in 19th century Canada, is that the growth happened too quickly and was unsustainable. Growing too quickly doesn’t allow for other parts of the industry to grow at a pace alongside it. This imbalance is unsustainable. If we’re in it for the long haul we should build on our strengths. Right now, we’re not even at a point where we could sustain mechanized weaving with our spinning capacity. Introducing cottage industry type looms that transition our knowledge of handlooms to step up to mechanization will allow us to create better fabric while growing our fibre and mill spinning.

What can people do to helps support this industry?

Education is key. People should learn about where there clothes come from and understand why they’re so cheap. Being informed by reading books like Overdressed by Elizabeth Cline or listening to podcasts like Magnifeco or following organizations like Fashion Takes Action is a good start to being an informed consumer. From there, making informed choices for clothing fall into place. A few recommendations would be buying second hand, buying some locally produced sustainable fashion like Peggy Sue Collection and repairing or upcycling your clothes.

What are potential area’s of waste that occur the weaving process?

The waste in handloom weaving occurs in the setting up process. When you tie the on a warp and cut off, you lose about 12 to 18” depending on your set up. You also waste in the sampling although you need a sample for testing and record keeping.

In many processes whether it’s food or textiles for example, waste is a by-product of convenience and speed. Just think of processed food which often ends up being thrown out not to mention the waste in empty calories. While producing large quantities of something can be cheap for the consumer, it often results in unforeseen or hidden costs either environmentally or socially. Manufacturing large quantities of anything and then dumping it onto the market drives the demand of the item down. When items are produced in too large a surplus, as happens today with fashion, we end up with too much of a bad thing which no one wants.

How can weaving be more sustainable?

Producing cloth whether by hand or machine is labour intensive. Like all manufactured products, textiles should be made to last decades if not a life time. Wearing them longer, washing them less often, getting accustomed to paying more for them, repairing them, upcycling and downcycling should be factored into their lifecycle.

Using natural biodegradable fibres is also key. When a textile using natural fibres has been used and worn out it can ultimately be composted. However, we are inundated with tonnes of synthetics. People are trying to wrap their heads around how to deal with recycling of these fibres. Natural fibres such as cotton and wool can be fairly easily recycled. A small proportion of recycled fibres can be added to new fibre without an appreciable difference in quality. Synthetic fibre is a little trickier to recycle. However, with the quantity of synthetics in existence, recycling technology for synthetics will definitely be a priority in the years to come.

The goal for sustainable textiles is to create a closed loop system. In this system, nothing ever has to go to landfill.

See more of Deborah’s weaving process on her instagram or connect with her via facebook.